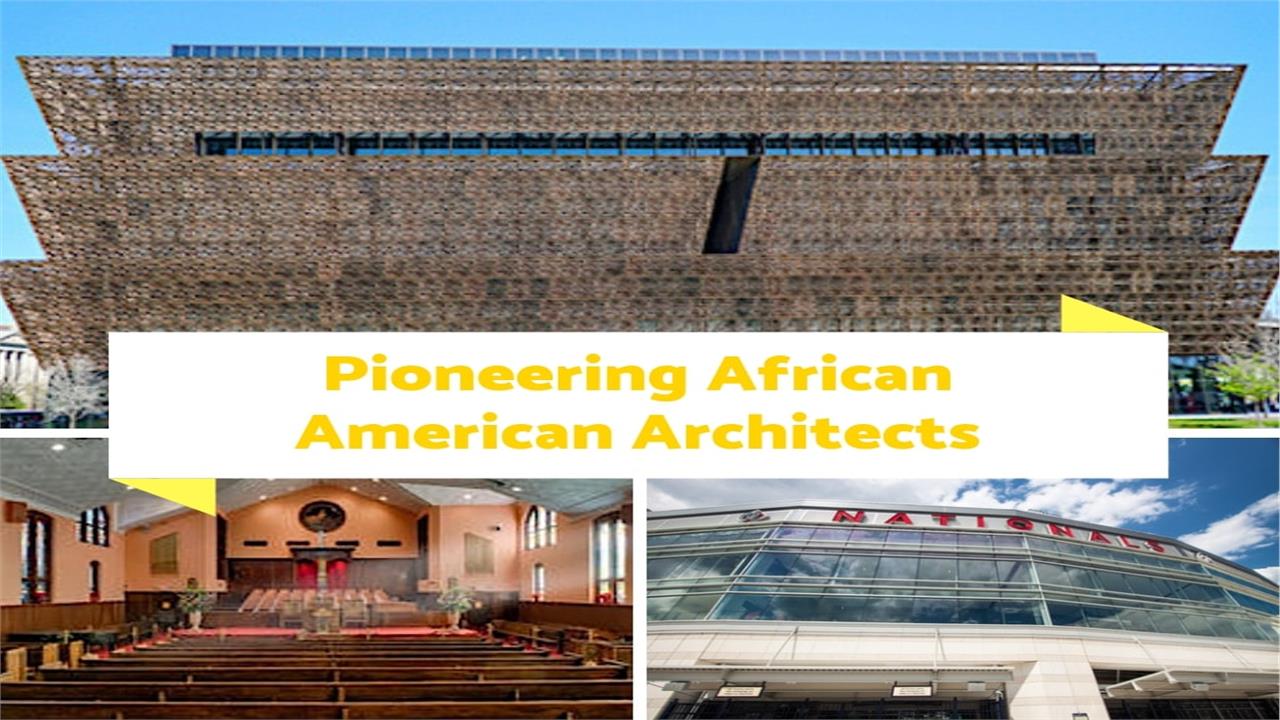

Profiles in Architecture and Design: Modern African-American Architects You Should Know About

By Rexy Legaspi | Updated May 14, 2022

Contemporary Black Architects Make Their Marks on Architecture and Design

At just over 100 years since Vertner Woodson Tandy was the first African American to be admitted to the American Institute of Architects, black architects have made an impressively lasting contribution to the U.S. architectural scene, not to mention American culture in general. And today’s crop of architectural professionals is no different, making more of an impact, it may be argued, than ever – from museums to sports buildings to government centers to airports and more.

While definitely a minority in their field, African-American architects have paved the way for future generations of architects – breaking social, cultural, gender, and color barriers in the process. We celebrate successful African-American architects who have thrived in the industry and achieved major accomplishments with their talent, creative vision, perseverance, and hard work.

Peter Cook: “… projects should positively impact communities and leave the world a better place in which to live.”

Greatly influenced by his great-grand-uncle Julian F. Abele, one of the first and most accomplished African-American architects in history, who designed the original campus of Duke University, Harvard’s Widener Library. and Philadelphia’s Free Library, Peter Cook desired to follow in Abele’s footsteps. Inspired by vivid memories of the time he spent in his great-grand uncle’s study listening to jazz, reading about modernism, and learning from Abele, Cook embraced the modernist approach to architecture. But while architecture is in his genes, it took several years for the designer in him to emerge and develop.

At a family friend’s advice, he enrolled in Harvard University’s Visual and Environmental Studies program. From 1986 to 1989, he was at Columbia University, earning a Master’s degree in Architecture – and soon after that, he accepted a position at D.C.-based Davis Brody Bond as an associate partner.

Cook once noted in an interview that one of the things he never tries to forget “… is that architecture ultimately comes down to the people who occupy the space.” So when Davis Brody Bond asked him to join the firm, he jumped at the opportunity because he thought the “firm never loses sight of the fact that architecture is artwork performed in a social setting.” This explains why most of his commissioned work focuses on designing buildings that engage a community and promote conversation and social interaction.

Take the opening in August 2010 of the Watha T. Daniel/Shaw Library in D.C.’s Shaw neighborhood – at its new location in 7th Street, N.W. in Washington, D.C. – when people from the community were lining up, eager to get into the library. Cook said that when he and his team “saw young kids and community members wanting to become a part of this building, we knew we had done something right. And it reminds me that this is why I got into architecture.” With its floor-to-ceiling glass windows and open floor design, the Reading Room of the Watha T. Daniel/Shaw Neighborhood Library is bright and airy. The Children’s area of the library follows the same design concept that makes it inviting and comfortable for visitors.

Cook’s outstanding portfolio of design and award-winning projects throughout the United States – particularly in the D.C. area – encompasses museums, memorials, embassies, libraries, cultural and learning centers, and mixed-used corporate and neighborhood master planning. In addition to the Watha T. Daniel Library, Cook’s work includes a number of notable buildings located in high-profile neighborhoods. Among them:

- The National Museum of African American History and Culture was a significant collaboration with Adjaye Associates, the Freelon Group, and Bond/Smith Group. Cook led the Davis Brody Bond team in the design of spaces that reflect the African-American experience throughout the Museum.

- The Dorothy I. Height/Benning Library is a two-story 22,000-square-foot library that replaced the original one-story brick building in D.C.’s Benning Heights, an area named after landowner William Benning, who helped finance the wooden bridge across the Anacostia River. The redesigned Benning Library includes a children’s room and separate reading areas for adults, teens, and children. The Teen Space at Benning includes computer stations and reading areas.

- St. Elizabeths East Gateway Pavilion/G8WAY DC is a multi-purpose building in the historic neighborhoods in Ward 8 designed for casual dining, a farmers’ market, and cultural/arts and community events. The Pavilion – spread over a two-acre plot – is a visible and welcoming site that features an open-air market for 40 vendors, a 21,000-square-foot green roof, and a raised park available for concerts, festivals, and large gatherings. All the spaces at St. Elizabeths East Gateway Pavilion – even the roof – are people-friendly. At the rear is an enclosed space for a community room, a café, and a restroom.

Today, Cook is the design principal at the D.C. Office of HGA Architects and Engineers. He works with HGA’s clients in the Washington, D.C., area and serves as a national design leader with an emphasis on cultural, civic, and federal projects across the country.

Marshall Purnell: "We didn't want to do additions to schools and firehouses and churches in the suburbs. We were in it to do main commercial structures that could be high design."

Considered one of the most accomplished African-American architects in the United States, Marshall Purnell, is the first African-American president of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), a past president of the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA), and co-founder/design principal of the firm DP+Partners, LLC, with the late Paul S. Devrouax. The Toledo, Ohio-born Purnell grew up in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and received his Bachelor of Science degree in Architecture and Urban Planning as well as a Master’s degree in Architecture from the University of Michigan.

After a year of teaching design at the University of Maryland, Purnell joined AIA. As a member of the Executive Office, he traveled all over the world to promote the society.

In 1978, he and Devrouax joined forces during the AIA Convention in Dallas, and they worked out of a tiny basement office in Dupont Circle for a few months before moving to a new “home” on Connecticut Avenue. One of their first jobs was a project to help design what would become the Frank D. Reeves Municipal Center at 14th and U Streets NW, Washington, D.C.

They worked on row houses; renovated historic buildings (Carnegie Library City Museum); designed a parking garage at Union Station, the Studio Theatre, and the African American Civil War Memorial, and built an information center at Howard University.

When DP+Partners, LLC, completed the 190,000-square foot addition to the Freddie Mac Campus in McLean, Virginia, it marked the first time an African-American-led architectural firm designed a headquarters building for a Fortune 500 Company. Situated in a 35-acre property in McLean, Virginia, the Freddie Mac headquarters is a 4-story 190,000-square-foot building “designed as a flexible and efficient structure that would respect the natural character of the wooded site and its relationship to the other campus buildings.” It was the springboard the firm needed to compete for the Potomac Electric Power Company (PEPCO) building.

In 2002, when the new PEPCO building opened, the Washington Post described it as a “fresh wind blowing down Ninth Street on a bright spring day" and "as sure-handed a piece of architectural urbanism as Washington has seen in many a moon." PEPCO was the first building in downtown Washington designed solely by African-American architects. The 10-story PEPCO headquarters includes 384,000 square feet of office space and 176,000 square feet of enclosed parking for 440 cars. There are magnificent views of the monuments and the Capitol from the rooftop deck and gardens.

Today, Purnell continues the creative vision that he and Devrouax intended for their firm. Among the huge projects completed are the Washington Convention Center; Washington Nationals Baseball Park; Verizon Center; National Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial; several projects for the Washington Metropolitan Area Transportation Authority; a marina, restaurant, luxury housing, and golf course in the Bahamas; and a number of projects on both the East and West coasts.

William Stanley III: “You derive great joy seeing people enjoy what you have designed. That is what it’s all about.”

Ivenue Love-Stanley: "Bringing design to underserved communities and to making design education … inclusive and accessible to all."

It was a meeting of “firsts” that day in 1972 when William Stanley III and Ivenue Love bumped into each other on the Georgia Tech campus. Stanley was graduating with the distinction of being the first African-American to complete a degree from Georgia Tech’s College of Architecture. And Ivenue Love was a freshman enrolled in the college. Five years later, she would become the first African-American woman to graduate from Georgia Tech’s College of Architecture – and become a licensed architect in the Southeast.

In 1978, William and Ivenue entered into two partnerships. They were married and started an architectural firm – Stanley Love-Stanley PC, an Atlanta-based company that today is the second-largest African-American architectural practice in the South.

Their initial collaboration was their first home. The two designed the house, worked on it, and in the process learned lessons about actual construction. The house was featured in Homes of Color Magazine in 2003. From that first project, the couple has worked together to bring different skills and personalities to their firm.

William Stanley III and Ivenue Love-Stanley are the first husband-and-wife to receive the American Institue of Architect’s (AIA) Whitney M. Young Jr. Award – given to an individual or organization working to pursue social justice and progressive values in architecture. Stanley received the award in 1995, and Love-Stanley was the 2014 recipient.

Stanley, who calls himself a “bon vivant,” is the principal designer; and Love-Stanley, described by her husband as “straight-laced and prim and proper,” manages the production side of the business. For this pair of opposites, the partnership has thrived and resulted in numerous community and professional service citations, as well as many award-winning landmark projects that have helped to reshape Atlanta and other communities throughout the region.

Considered their best-known work, the New Horizon Sanctuary, Ebenezer Baptist Church, is a 34,000-square-foot-structure that includes a 1,600-seat sanctuary, educational building, peace plaza, bell tower, and a prayer garden.

One of their highlights was a huge project for their alma mater: the design of the Olympic Aquatic Center at Georgia Tech. The new complex was the centerpiece of the 1996 Olympic competitions for swimming, diving, synchronized swimming, and water polo. The center features 4,000 permanent seats and room for 11,000 temporary seats. The firm participated as a 50 percent joint venture partner.

Other projects include

- The historic renovation of Reynolds Cottage, the residence of the President of Spelman College (Atlanta), included improvements to the structural, mechanical, and electrical infrastructure. The 23,000-square-foot cottage serves as a reception facility for visiting dignitaries as well as the home of the school’s president.

- The Lyke House Catholic Student Center at Atlanta University was completed in 1999 and received a design excellence award from the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA). Its unusual design is a replication of churches built by Ethiopia’s King Lalibela from hewn rocks to celebrate African Christian antiquity. The 12,000-square-foot Center houses a chapel, student center, and rectory.

- Agricultural Sciences Building at Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College (Tifton, Georgia) – For this project, Stanley Love-Stanley participated as an associate firm responsible for programming, design, and the initiation of construction documents for a state-of-the-art Agricultural Sciences Research and Teaching Facility. The building is a 1-story structure built on a sloping 5-acre parcel on the grounds of the college and includes panoramic views of a catfish pond, historic farmscape, and rolling meadow.

As Stanley and Love-Stanley add to the sights of Atlanta’s skyline, they continue to use their knowledge and experience to improve neighborhoods and make them architecturally relevant.

David Frank Adjaye: Architect with “An Artist’s Sensibility and Vision”; founder and principal architect of New York and London-based architectural firm AdjayeAssociates

Photo credit: David Adjaye by Rossi101 under license CC BY-SA 3.0

A major figure of his generation, David Adjaye is internationally acclaimed for his diverse designs and creative uses of materials and light. His interests and focus range from contemporary art, music, and science to African art forms and the civic life of cities.

The New York and London-based architect was born in Tanzania to Ghanaian parents. Because his father was a diplomat, Adjaye lived in Egypt, Lebanon, and other countries and, at an early age and was exposed to different cultures and architectural styles.

When his family settled in London, Adjaye attended London South Bank University, where he earned a Bachelor’s degree in Architecture. While studying for his degrees, Adjaye worked at several architectural firms in London. In 1994, a year after he received a Master’s in Architecture from the Royal College of Art, he formed Adjaye and Russell. Six years later – in 2000 – he established Adjaye Associates.

Among the firm’s early projects were studios, restaurants, retail stores, and private residences. Eventually, the work expanded to public buildings, community centers, and museums.

One of Adjaye's projects, The Museum of Contemporary Art in Denver – built in 2007 – is the official home for contemporary art in Denver. While there is no permanent collection at the Museum, there are rotating exhibits.

In 2009, Adjaye received his most prestigious assignment when he became a part of the Freelon Adjaye Bond/Smith Group (FAB) team, selected to design the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

Awarded an OBE (Order of the British Empire) in 2007, Adjaye was recently knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for his contributions to architecture. He has taught at the Royal College of Art and the Architectural Association School in London, and has held distinguished professorships at the University of Pennsylvania, Yale, and Princeton.

Today, Adjaye divides his time between his London and New York City offices, where he works on various design projects.

Philip Freelon: Creating Beauty in Everyday Life; Co-designer of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

For Philip Freelon, designing the new Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture was not only a professional honor but also a rewarding personal moment. Growing up in the ‘60s and ‘70s, Freelon recalled the “black pride days” and the time his father participated in the March on Washington and heard Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech – not too far from the very spot that the new museum now stands.

Acclaimed as one of the country’s most successful and talented architects, Freelon formed the Durham, North Carolina-based Freelon Group in 1990. In 2014, Freelon’s company joined the Perkins+Will global firm – making the merged group the largest architectural firm in North Carolina. He heads the Research Triangle Park and Charlotte Offices and is a key leader of the firm’s cultural and civic practice.

A native of Philadelphia, Freelon received his Bachelor of Environmental Design degree in Architecture from North Carolina State University and his Master’s degree in architecture from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He has served as an adjunct faculty member and lecturer at a number of prestigious universities, including Harvard, MIT, the University of Maryland, Syracuse University, Auburn University, the University of Utah, and the California College of the Arts. He is currently on the faculty at MIT’s School of Architecture and Planning.

Freelon’s success is rooted in architecture that engages the community and enhances the lives of everyday people. He has stated that he likes “to create beauty in everyday lives” – a mindset that has defined his work in the public sector, with projects like libraries, museums, and government buildings.

His firm has designed a number of cultural and educational buildings in North Carolina and across the U.S. Among their projects is the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture in Charlotte, and the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco, which features a glass wall, a transparent stair, and a handrail system that is visible from the street.

Curtis Moody: “Responsive Architecture” Style; CEO and president of Columbus, Ohio-based Moody Nolan, the largest African-American-owned architecture firm in the U.S

“Just an architect. A really good one.” That’s how Curtis Moody, one of the country’s premier African-American architects, wants to be defined.

In 1982, in the midst of an economic downturn, Moody started his practice in a house in Columbus, Ohio – and a year later, counted nine employees in his fledgling architectural firm. As Moody established a reputation as a great talent, he attracted more clients; and in 1984, he partnered with Howard Nolan to form Moody Nolan.

A basketball player for Ohio State University in the early 70s, Moody channeled his passion for athletics into a successful business: designing sports and recreation facilities for cities, colleges, and universities. His impressive work on the Jerome Schottenstein Center – a multi-purpose athletic venue on the campus of Ohio State U – cemented his reputation as an architect and that of his firm.

While Moody has distinguished himself in the sports facilities field, he also works on diverse projects, including fire stations, performing arts centers, libraries, schools, public service buildings, and more. Whether in Columbus, Cincinnati, Cleveland, or another city in the U.S., Moody and his firm “create functional yet iconic design statements” – not only addressing a “client’s unique vision” but taking it to another level: a style Moody calls “responsive architecture.”

In almost 40 years as an architect, Moody has designed more than $4 billion of building construction and received 26 design awards from the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA), more than any other minority firm in the country.

A 1973 graduate of Ohio State University with a Bachelor of Science degree in Architecture, Moody studied Urban School Planning & Design at Harvard Graduate School of Design. He is a winner of the prestigious Whitney M. Young, Jr. award as an outstanding African American Architect in the United States.

Allison Williams: From Art to Architecture; Vice President and Director of Design for AECOM’s U.S. West Region

Growing up in a home that was visually based – her father was an engineer-urban designer who built their home in Cleveland, and her mother was a journalist and very artistic – Allison Williams was naturally drawn to art and its expression. She received her undergraduate degree in the practice of art at the University of California-Berkeley. Surrounded by artists in Berkeley but frustrated with the uncertainty of art as a career, Williams enrolled in a Masters of Architecture program at Berkeley.

Inspired by her father and mentors at architectural firms early in her career, Williams brought her passion, creative vision, and talent into her work – eventually becoming a prominent and respected architect.

In more than 30 years in the field, Williams has designed major projects in the San Francisco Bay Area, in other major cities across the U.S. and the world. Her work extends to civic, cultural, commercial, corporate, and research facilities. Among her significant large-scale projects is the International Terminal at San Francisco International Airport, the Princess Nora Bint Abdulrahman University Health Sciences and Research Campus (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), a research facility in Singapore, and the August Wilson Center for African American Culture in Pittsburgh, which is named after the renowned playwright and celebrates the contributions of African Americans to American culture, art, music, and theatre in the region and globally … past, present, and future.

A recipient of The Loeb Fellowship at Harvard Graduate School of Design, Williams was elevated to Fellow in the American Institute of Architects in 1997. She is a member of the Harvard Design Magazine Practitioners Board and past-Chair of Public Architecture's Board of Directors. Williams is a frequent lecturer and a Peer Reviewer for the GSA Design Excellence Program and as a juror for the 2011 AIA National Design Awards.

At the 2015 AIA Women’s Leadership Summit, Williams urged attendees to “stay true to themselves, do what they love doing, and do it without being apologetic.” She said: “We’re here because we’re architects and passionate, not because we’re women.”

Additional Resources: